The Top 3 Crypto Security Best Practices Every Investor Needs

Hey crypto fam 🔐

Ivan Bianco, a Brazilian crypto blogger, once decided to show his audience how he sets up a wallet during a live stream. He opened a text file containing his passwords, forgetting that the same file also included the seed phrase for his main wallet. Viewers saw the phrase on screen for just a couple of seconds. That was enough: within minutes, about $60,000 was drained from his account. The most ironic part was that he realized what had happened live on air, when he saw the outgoing transaction appear in a blockchain explorer.

It’s a very sad story, isn’t it?

If you want to avoid incidents like this, check out our short guide on advanced crypto security.

Multisig and Distributed Custody: What This Looks Like in Real Life

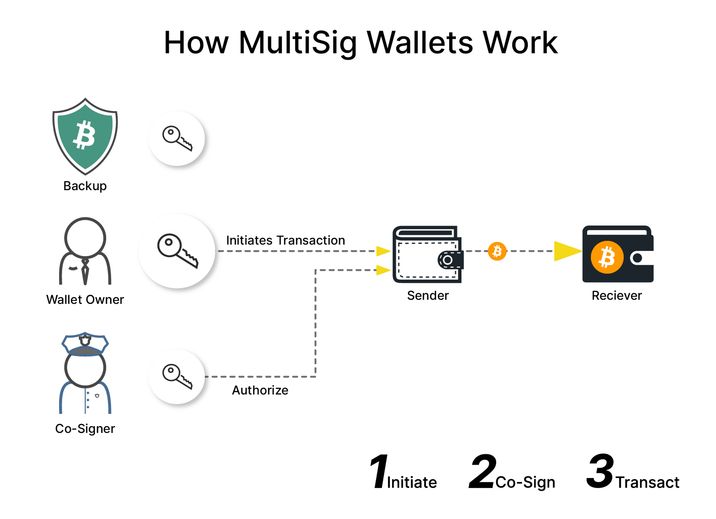

In a standard self-custody crypto wallet, everything depends on one seed phrase or private key, and whoever controls it has full control over the funds. This is convenient, but extremely fragile: one mistake, or one leak, and control is lost. Multisig addresses this exact problem by removing the situation where a single secret represents total ownership.

In practice, multisig is not an “extra password” or a “stronger seed.” Funds are held at an address or smart contract that cannot move assets at all unless it receives multiple independent approvals. Even if one key is stolen or compromised, that key alone is useless.

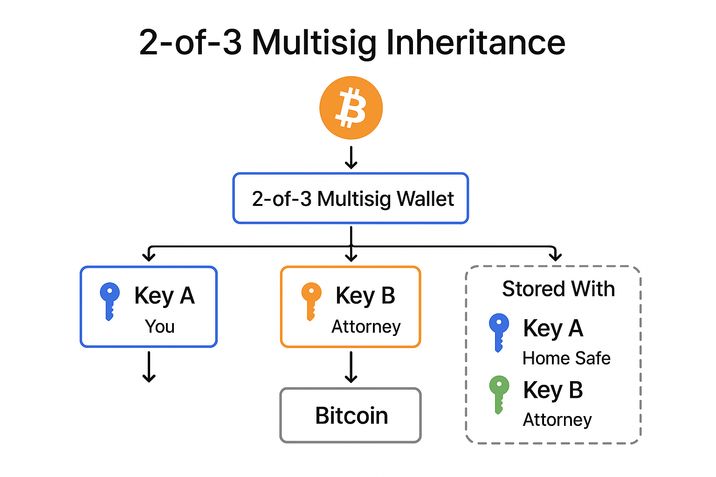

Consider the most common and practical setup: a “2-of-3” multisig. A person creates three independent keys. The important point is that these are three separate wallets, each with its own seed phrase, generated independently. They are not copies or derivatives of one another. Each key is equal and standalone.

A rule is then defined: any transaction must be approved by any two of the three keys. This rule is not informal or procedural — it is enforced at the protocol level. In Bitcoin-like systems it is encoded into the address itself. In Ethereum and EVM-based systems it is enforced by a smart contract. In practice, the most widely used implementation is a smart-contract wallet such as Safe, which exists specifically to enforce multisignature control.

From that moment on, funds are no longer sent to a “wallet” in the usual sense. They are sent to a multisig contract. This is where the everyday user experience changes in an important way. When the owner wants to send funds, they are not actually executing a transaction immediately. One key simply proposes a transaction: it specifies the recipient and amount and adds its signature. At this stage, nothing moves. The funds remain exactly where they are.

A second key, usually on a different device and often in a different physical location, then reviews that same proposed transaction. The user verifies the address and the amount and adds a second signature. Only when the required threshold — two signatures out of three — is reached does the contract allow the transaction to execute. The third key may never be involved at all. Its role is redundancy and risk distribution.

This structure has very real consequences. If one key is stolen, nothing happens. The attacker cannot move funds with a single signature. If one key is lost, access is not lost, because the remaining two keys are sufficient. Even if a user is tricked into signing something malicious, the damage usually stops at the second step: without a second independent confirmation, the transaction cannot complete.

One of the most common mistakes beginners make is ignoring where and how the keys are stored. Multisig only works if keys are actually separated — both physically and logically. A mature setup typically looks like this:

- one hardware wallet used for regular operations and kept at home,

- the second hardware wallet stored in a different physical location such as an office, a safe, or with a trusted family member,

- the third key was kept strictly as a backup for recovery scenarios.

If all keys are stored in the same place, multisig becomes an illusion rather than real security.

It is also important to understand that multisig is not a case of “more complexity equals more security.” One of the most common failure modes is overengineering a scheme that becomes difficult — or frightening — to use. A good multisig setup is one you can clearly explain to yourself a year later without diagrams or instructions. If the system intimidates you, it is already unsafe.

Air-Gapped Systems: What They Really Are, How They Work, and How They Differ from Cold Wallets

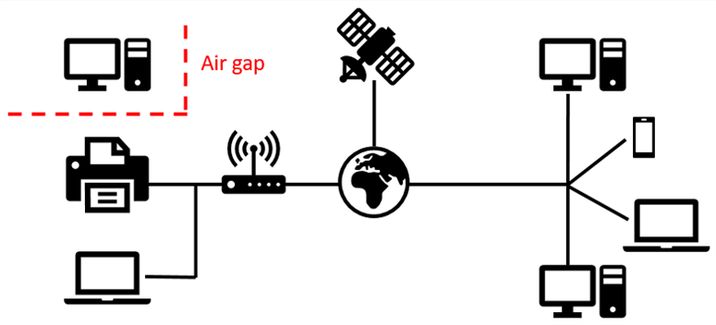

The term air-gapped comes from classical information security and military systems, where it literally means that a system is separated from other networks by an “air gap” — a physical absence of connectivity. A truly air-gapped system has no direct network connection and therefore cannot be accessed remotely over the internet.

In the context of self-custody wallets, an air-gapped system is a way of storing and using private keys such that the device holding those keys never connects to the internet and never directly interfaces with an online computer. No Wi-Fi, no Bluetooth, no USB cable. Interaction with the outside world happens only through constrained, indirect channels such as QR codes or removable media like microSD cards.

This is where an important distinction must be made, because it is one of the most common sources of confusion: air-gapped systems and cold wallets are not the same thing, even though they overlap.

A cold wallet is any setup where private keys are kept away from continuous internet exposure. A paper wallet is cold storage. A hardware wallet is cold storage.

An air-gapped device is designed so that direct electronic communication with online systems is physically impossible. You cannot simply plug it into a computer and sign a transaction. This means the transaction process is split across two separate environments. An online computer is used only to prepare data. It constructs an unsigned transaction — essentially a structured description of what you want to do, such as sending a certain amount to a specific address. That computer cannot sign anything, because it has no access to private keys.

The unsigned transaction is then transferred to the offline device using a method that does not create a live connection. This might be done by displaying a QR code that the offline device scans with its camera, or by copying a file onto a memory card and physically inserting it into the device. The offline device, operating in isolation, verifies the details and signs the transaction using a private key that never leaves that environment.

The signed transaction is then transferred back to the online computer using the same disconnected method. The online computer simply broadcasts it to the network. It acts as a courier, not as part of the trusted security boundary.

The core security benefit of this architecture is that even a fully compromised computer cannot directly attack the private keys. It cannot send arbitrary commands, cannot silently request signatures, and cannot exfiltrate secrets through an interface. The only thing it can do is attempt to trick the user by presenting a malicious transaction. That is why air-gapped systems rely heavily on the offline device having its own screen and on the user carefully verifying addresses and amounts before approving anything.

This leads to an important clarification: air-gapping is not “absolute security.” It is a reallocation of risk.

Transaction Hygiene: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Practice It

Transaction hygiene is the discipline of interacting with blockchains consciously and deliberately, with a clear understanding of what you are signing and what rights you are granting. In crypto, funds are rarely lost because private keys are hacked. Much more often, users lose money because they themselves authorize everything required — by approving a contract, signing a message, or confirming a transaction without fully understanding the consequences.

Unlike traditional banking, a blockchain signature does not always mean an immediate transfer of funds. In many cases, it grants long-term permissions, delegates control, or authorizes actions that may be executed later. This is why blindly clicking “Confirm” is one of the most dangerous habits in crypto. Even hardware wallets or air-gapped setups cannot protect you if you sign without understanding what you are approving.

The most common risk area is smart contract permissions. When you approve a token, you are not sending it — you are allowing a contract to spend it on your behalf. If that approval is unlimited, it is effectively a transfer of control. Over time, wallets accumulate many forgotten approvals, and these lingering permissions are one of the primary vectors for theft.

Another especially dangerous category involves signatures that are not transactions. Users are often asked to “just sign a message” to log in, verify ownership, or claim something. These signatures cost no gas and appear harmless, but they can later be used to grant permissions or enable asset transfers. If you do not understand exactly what a signature does, that alone is a reason to stop.

Practicing transaction hygiene is ultimately about changing your mental model. Every signature should be treated not as a button click, but as a program execution with irreversible consequences. Before approving anything, you should verify addresses, amounts, and the source of the request, and understand whether you are granting a one-time action or ongoing authority. Periodically reviewing and revoking old permissions is a basic security practice, not paranoia.

You can build the most sophisticated security architecture — cold keys, hardware wallets, air-gapped devices, multisig but if you ignore basic common sense and routinely break your own rules, that protection quickly becomes meaningless. Advanced security is not defined by the tools you use, but by the habits you maintain. Technology only enforces discipline; it cannot replace it. In practice, real security always starts with behavior, and only then is reinforced by technical safeguards.